At $36.2 trillion in mid-2025, the U.S. national debt has risen to an unusual high and is roughly equal to the nation’s yearly GDP. This article examines the structure of U.S. debt, identifies the primary holders (domestic and foreign), and analyzes the economic, political, and social implications of continuous borrowing. We highlight the impending issues of growing interest rates, reliance on foreign sources, and intergenerational equity by placing U.S. debt in historical and comparative contexts. While the United States benefits from deep financial markets and the dollar’s status as a reserve currency, unchecked debt growth poses risks to fiscal stability and policy flexibility in the coming decades.

The U.S. national debt refers to money owed to foreign institutions or governments to make up for revenue shortfalls. It is also critical to the country’s economic stability, public investment, and the future policies of the United States. As of 2025, the federal debt has surpassed $36 trillion, an increment of 97.9% since 2015. (USAFacts, Fiscal Data). The scale and structure of this debt raise critical questions about sustainability, investor confidence, and the trade-offs between servicing debt and financing public priorities such as education, healthcare, and infrastructure.

This article seeks to answer three central questions:

- Who holds the U.S. debt?

- What types of debt exist, and how are they structured?

- What are the long-term implications of sustained borrowing?

What Kind of Debt Exists?

The federal debt of the United States is broadly divided into two categories: marketable and non-marketable securities. Marketable securities, such as Treasury bills, notes, and bonds, are traded on secondary markets and widely held by domestic and international investors. Non-marketable securities, such as US savings bonds and special Treasury securities, cannot be sold and are usually held by individuals or government trust funds.

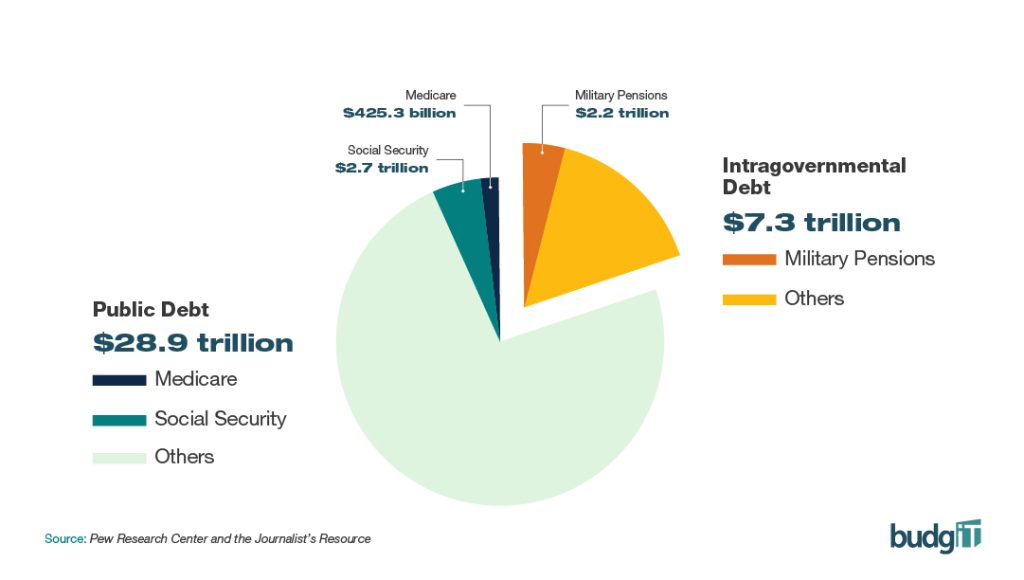

Another key distinction is between public debt and intragovernmental debt. Public debt refers to federal debt that is owned by individuals, corporations, state or local governments, foreign governments, and other entities outside the U.S. government. This type of debt is the primary debt often discussed because it represents the money the U.S. government owes to external parties, and is often the largest, generally comprising 80% of the national debt. The U.S. owes about 28.9 trillion in public debt. Intragovernmental debt is the portion of the national debt that the government owes to itself. This type of debt is another, and one part of the government, such as Social Security, invests its surplus funds in special treasury securities. So this debt is technically money owed from one government account to another and typically comprises 20% of the national debt. Currently, intragovernmental debt amounts to about $7.3 trillion.

Figure 1: Breakdown of U.S. Debt Composition (2025)

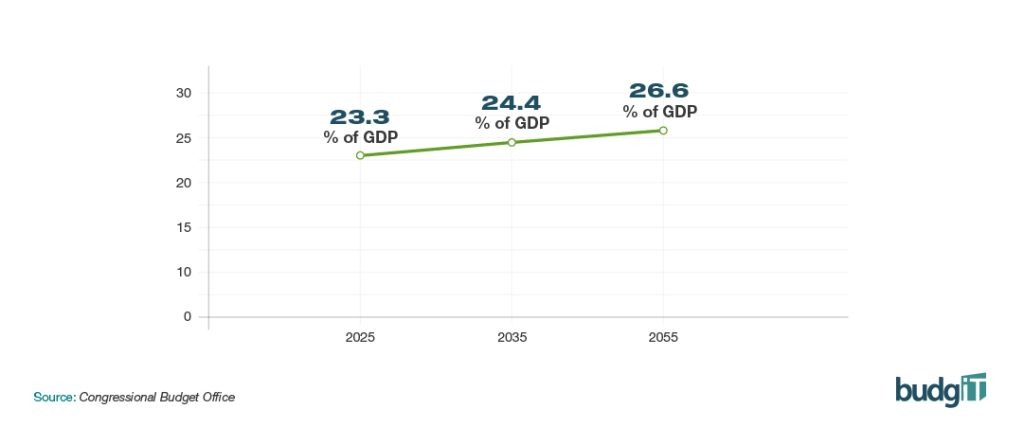

Rising deficits are at the root of increased national debt values. In FY 2025, the federal government projected $7 trillion in spending but only $5.16 trillion in revenue, leaving a $1.8 trillion gap that must be bridged through borrowing (Wall Street Journal, Vox, Peterson Foundation). Due to the disparity between revenue and spending, the Congressional Budget Office predicts that federal spending will rise from 23.3 percent of GDP in 2025 to 26.6 percent in 2055 (CBO).

Who Holds the Debt?

Currently, about $28-29 trillion of the national debt is held by the public. This is money owed to investors, foreign governments, the Federal Reserve, and individual lenders. The largest single institutional holder of U.S. debt is the Federal Reserve, with more than $4 trillion in Treasury securities, nearly double its pre-COVID holdings. Domestic private investors, including mutual funds, pension funds, banks, and insurers, hold about two-thirds of the remaining public debt.

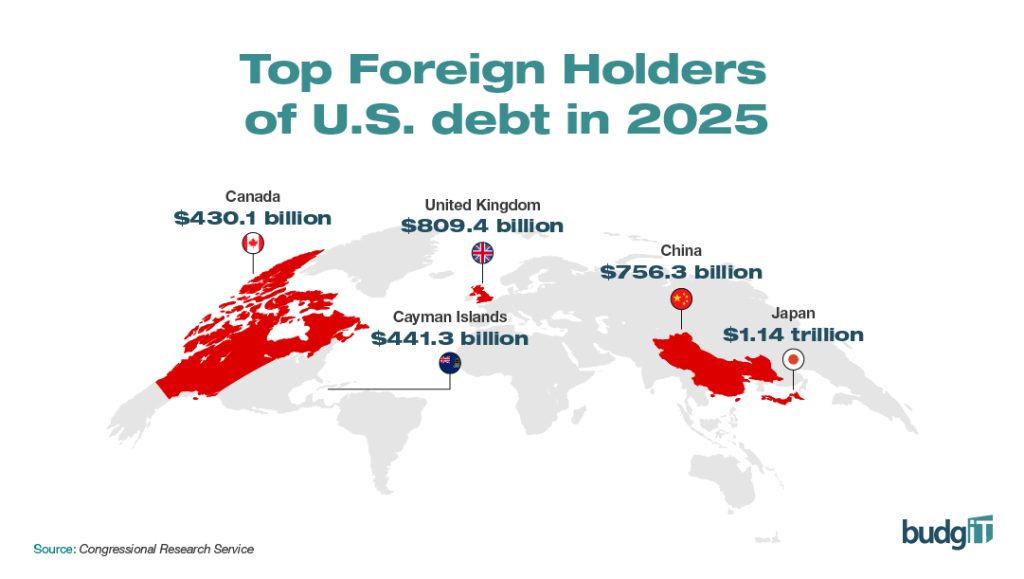

One-third of U.S. public debt ($9 trillion, 31%) is held by foreign governments and foreign private investors. As of March 2025, the top five foreign holders of federal debt are Japan ($1.14 trillion), the United Kingdom ($809.4 billion), China ($756.3 billion), the Cayman Islands ($441.3 billion), and Canada ($430.1 billion). According to the Congressional Research Service, about 44% of total foreign debt is held by governments, and about 56% is held by private investors.

Figure 2. Top Foreign Holders of U.S. Debt, 2025.

Fiscal Trends and Context

Persistent budget deficits drive the growth of U.S. debt. In FY 2025, the federal government projected expenditures of $7 trillion against revenues of $5.16 trillion, resulting in a $1.8 trillion deficit. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts federal spending to rise from 23.3% of GDP in 2025 to 26.6% by 2055, largely due to aging demographics, healthcare obligations, and interest costs.

Figure 3: Debt-to-GDP Ratio Trend

What are the implications of continuous borrowing?

Rising Interest Payments: Besides owing enormous amounts of money, one of the major implications of constant borrowing is the interest costs that rise as more money is borrowed. Interest payments have surged from $497 billion in 2022 to over $900 billion in 2024, consuming nearly 17% of total federal spending. As debt rises and interest rates fluctuate, servicing costs will constrain fiscal flexibility, limiting resources for essential programs.

Economic Crowding Out: Heavy federal borrowing can reduce the availability of credit for businesses and households. The impact of this is slowed or halted investment and growth, which affects the economic health of the nation, as there is limited access to capital.

Foreign Dependence and Credit Risk: Relying on foreign holders creates vulnerabilities. For instance, if foreign investors decide to reduce their holdings, borrowing costs may rise because they would need to fit the expected yields on Treasury securities. When this happens, credit rates will be downgraded, and there will be a strain on the market, as seen with the 2011 S&P downgrade of US debt.

Policy Trade-offs: As more of the budget is devoted to debt repayment, public investment in infrastructure, innovation, and social programs may fall, which results in difficult trade-offs between short-term stability and long-term competitiveness.

Intergenerational Equity: High levels of debt effectively transfer fiscal burdens to future generations. Younger citizens will inherit constraints on economic policy, reduced fiscal space, and potentially higher taxes.

Conclusion: Why You Should Pay Attention

The U.S. debt not only impacts the government, but it also affects access to public services. As interest on debt increases, more of the budget will go toward offsetting interest, and this will cause fewer resources to be available for education, infrastructure, and healthcare, which will impact you as a citizen. Also, national debt shapes the priorities for policies. If debt continues to increase, more policies around reducing it will supersede any policies concerning public programs, subsidies, and resources that would otherwise be helpful to citizens.

The U.S. debt not only impacts the government, but it also affects access to public services. As interest on debt increases, more of the budget will go toward offsetting interest, and this will cause fewer resources to be available for education, infrastructure, and healthcare, which will impact you as a citizen. Additionally, national debt shapes the priorities for policies. If debt continues to increase, more policies around reducing it will supersede any policies concerning public programs, subsidies, and resources that would otherwise be advantageous to citizens.

Without corrective action, debt will increasingly constrain U.S. policy choices, economic competitiveness, and social investment, directly affecting current and future generations. The US government must prioritize reducing deficits by expanding revenue increases and reducing its spending priorities. It must also increase public understanding of debt dynamics to enhance accountability while maintaining stable relationships with major foreign creditors to reduce geopolitical risks.

References

- Congressional Budget Office (CBO). The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2055.

- Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Federal Debt: A Primer

- Congressional Research Service. Foreign Holdings of U.S. Debt.

- Peterson Foundation. U.S. Debt and Deficits Explainer.

- The Journalists Resource. The National Debt: How and Why the US Borrows Money.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. Fiscal Data.

- USAFacts. National Debt Tracker.

- Vox. Explainer on U.S. Borrowing and Deficits.

- Wall Street Journal. Coverage on FY 2025 Budget.

Abiola Afolabi, International Growth Lead at BudgIT, and Rebecca Nzerem, Communications Officer at BudgIT, write from Chicago, IL.